The impact of liquid nitrogen freezing on coalbed methane (CBM) production in coal reservoirs has been widely studied, but little research has focused on the thawing process. In this study, we investigated the effects of microwave thawing on coal frozen by liquid nitrogen with different moisture contents using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), longitudinal wave velocity, and infrared thermal imaging technologies. The results show that as the moisture content increases, the growth rate of the seepage pores in air-thawed samples gradually increases. Compared to air thawing, the seepage pore increase rate after microwave thawing under dry, wet, and saturated conditions increased by 17.37%, 9.56%, and 9.32%, respectively. The velocity results were similar to those of the seepage pore growth rate. The uniformity of surface temperature in microwave-thawed samples is related to the initial moisture content. During liquid nitrogen freezing, low initial moisture content favors the formation of surface cracks. After microwave thawing, the pore water decreased by 21.46%, 44.85%, and 21.31% in dry, wet, and saturated samples, respectively. The study suggests that microwave thawing not only improves the pore structure of coal but also removes moisture from the pores.

Coalbed methane (CBM) is collected before mining, ensuring both mining safety and providing energy. However, the low permeability of coal reservoirs restricts large-scale, continuous extraction of CBM. To enhance reservoir permeability, techniques such as hydraulic fracturing have been employed. Hydraulic fracturing requires large amounts of water, leading to valuable energy consumption, pollution in water-scarce regions, and induced seismicity. Due to these issues, waterless fracturing methods (such as liquid nitrogen fracturing) have been considered an economically and environmentally friendly technology. Liquid nitrogen fracturing includes freezing and thawing stages. However, current researchers believe that the melting phase (air thawing phase) has little impact on the measured samples, or it is a negligible part of the entire fracturing process. The air thawing stage in conventional liquid nitrogen fracturing has a minor effect on the fracturing outcome, mainly focusing on the pore structure. However, the improvement of rock permeability depends not only on the pore structure but also on the moisture content and other moisture conditions. To further enhance the stimulating effect of liquid nitrogen, we propose a new method of using microwaves instead of air thawing for coal frozen with liquid nitrogen. The fracturing effect is primarily manifested in pore structure evolution and moisture variation. Therefore, it is crucial to quantitatively describe the evolution of the pore structure and the moisture variation during the treatment process. Low-field nuclear magnetic resonance can non-destructively reflect the pore structure of samples before and after treatment. By analyzing the T2 spectra, the fracturing effect of microwave radiation on liquid nitrogen-frozen coal was systematically studied. This study demonstrates the pore structure and temperature response of coal samples with different moisture contents under the combined effect of liquid nitrogen and microwaves.

In this study, the material used is bituminous coal (25mm × 50mm), and the pore structure evolution and moisture variation of the coal were obtained using a low-field NMR device, manufactured by Suzhou Newmai Analysis Instruments Co., Ltd., model: MacroMR12-150H-I.

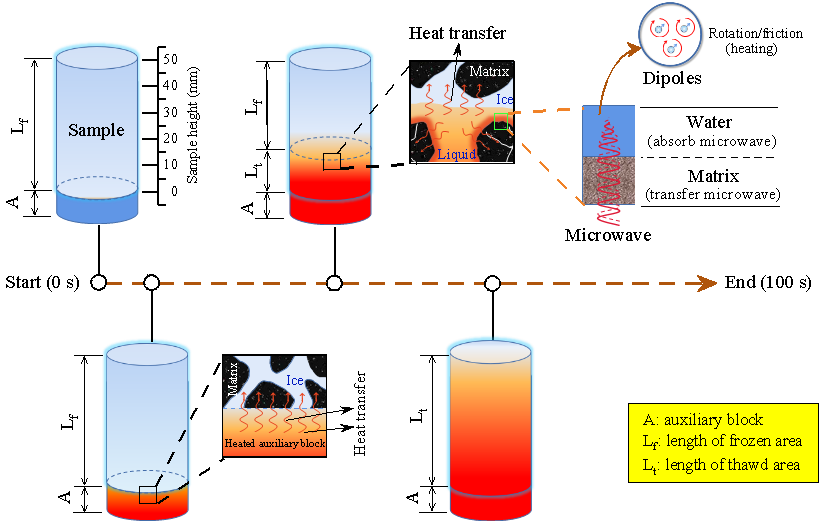

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of thawing process

The experimental procedure is as follows:

(1) The coal samples are dried in a drying oven at 60℃ for 12 hours. The saturation step involves applying -1 MPa vacuum for 6 hours, followed by pressurizing the samples in water at 20 MPa for 24 hours using a vacuum pressure water saturation device.

(2) Dry, wet, and saturated samples are prepared by weight method.

(3) The dried and wet samples are subjected to NMR testing again to obtain the initial moisture content inside the samples.

(4) The samples are immersed in a container filled with liquid nitrogen.

(5) The frozen samples are immediately thawed in a 5 kW microwave oven for 100 seconds. Note that a saturated water auxiliary block is placed at one end of the frozen sample, close to the environment temperature (18.5℃), to aid the thawing process, as shown in Figure 1.

(6) After thawing, the samples are removed from the microwave and temperature tests are conducted using a thermal imaging camera.

(7) Once the temperature of the thawed coal samples returns to room temperature, NMR testing is performed again to obtain the residual moisture content inside the samples.

At the same time, another set of frozen samples is thawed under air conditions. Finally, the thawed samples are subjected to drying, saturation, NMR, drying, and ultrasonic measurements.

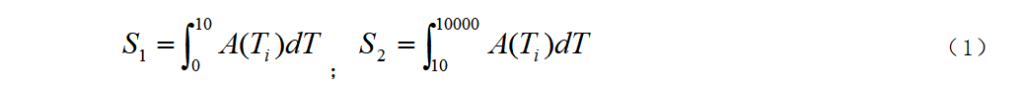

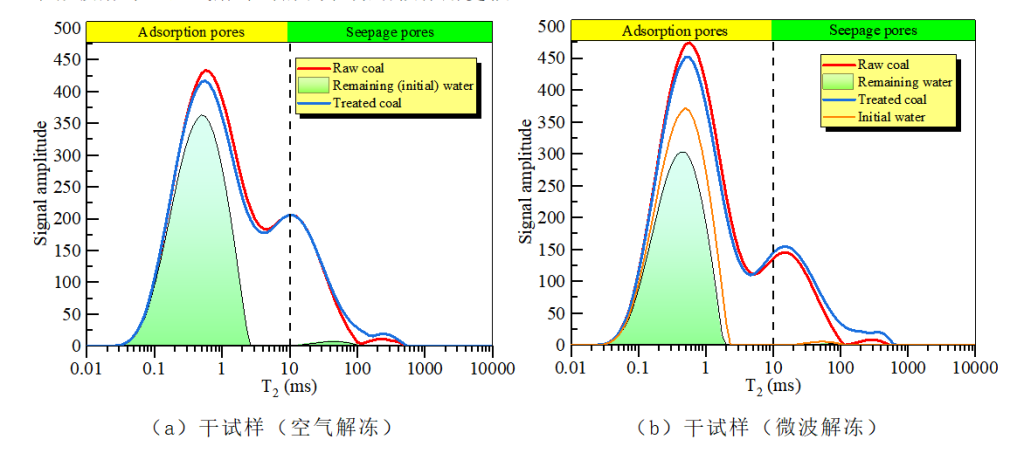

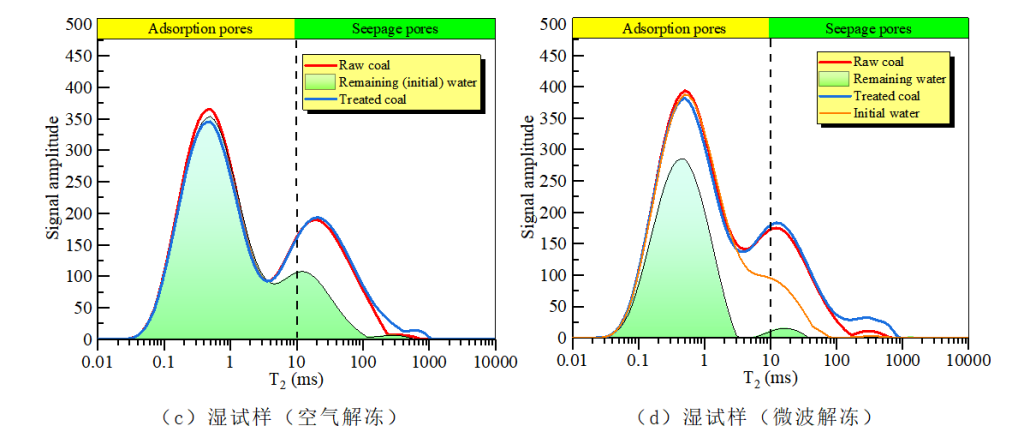

The authors measured the T2 spectra of coal samples before and after treatment using low-field nuclear magnetic resonance technology. Figure 2 shows the T2 spectra of coal samples. After freeze-thaw treatment, the T2 curve of the sample (treated coal) shifts to the right, and the amplitude of the second peak increases. These changes indicate an increase in both the size and number of the coal pores after treatment. Additionally, the enhancement of the T2 spectra by microwave thawing is more significant than air thawing, suggesting that microwave thawing is more effective in destroying the coal pore structure compared to air thawing. Coal pores are divided into micropores, mesopores, and macropores (or cracks), corresponding to T2 size ranges of 0.1ms-10ms, 10ms-100ms, and 100ms-10000ms, respectively. Micropores are defined as adsorption pores, and mesopores and macropores (or cracks) are defined as seepage pores, which provide channels for gas diffusion and flow. Therefore, the peak area Si corresponding to adsorption pores and seepage pores can be calculated by the following equation:

In the equation, A is the signal amplitude at Ti time; i = 1, 2 corresponds to adsorption pores and seepage pores, respectively.

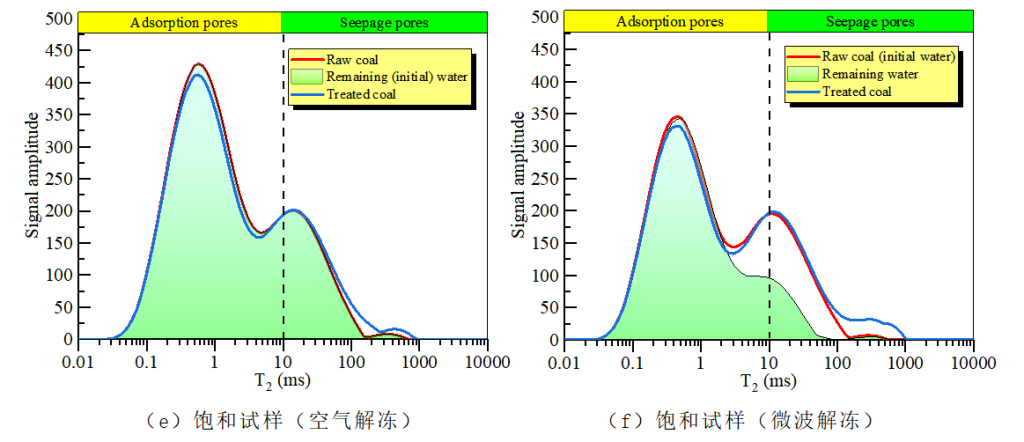

According to the peak area variation results (Figure 3), after freeze-thaw treatment, the adsorption pores and total pores of the sample did not change much, and the change rate with increasing saturation was not obvious. The results show that under the same freezing time, the growth rate of microwave-thawed samples is greater than that of air-thawed samples, with a more significant improvement in the growth rate of low-saturation samples. For example, compared to air thawing, the seepage pore increase rate in saturated samples increased by 9.32%, in wet samples by 9.56%, and in dry samples by 17.37%. This confirms that microwave thawing has a stronger effect on enhancing the pores in coal than air thawing.

Figure 2: T2 curves of air-thawed and microwave-thawed coal samples

Figure 3: Pore growth rate of treated coal samples

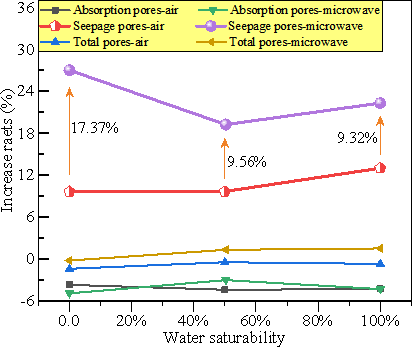

In the liquid nitrogen fracturing mechanism, the freezing expansion force generated at low temperatures is the main cause of freeze-thaw damage to coal samples with moisture content. As shown in Figure 4, low saturation samples provide extra expansion space for the phase change of water into ice, reducing the freezing expansion effect. Generally, the degree of damage to coal samples by liquid nitrogen increases with higher moisture saturation. This is why the freezing effect of liquid nitrogen is better in 100% saturated samples than in 50% saturated ones. Due to the selective heating of microwaves and the uneven thermal effects between coal elements, thermal stress is induced in the coal. Additionally, as the temperature rises during the microwave process, the vaporization of water creates high-pressure steam within the coal pores, promoting the expansion and interconnection of pores/cracks (Figure 4). Therefore, after microwave thawing, the pore structure is further enhanced. This improvement is negatively correlated with moisture content. After microwave thawing, the T2 curve areas of dry, wet, and saturated samples decreased by 21.46%, 44.85%, and 21.31%, respectively. This indicates that microwave thawing removes some pore water within the coal samples.

Figure 4: Damage to the matrix and pore water changes after liquid nitrogen and microwave treatment

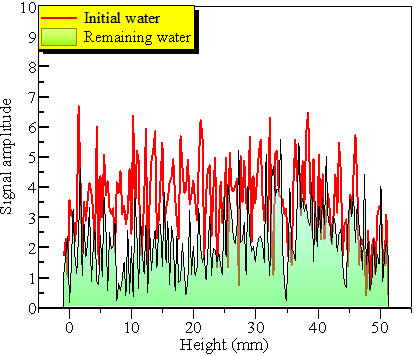

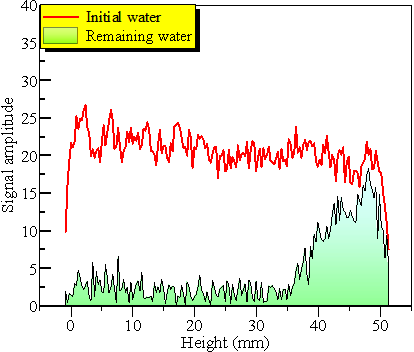

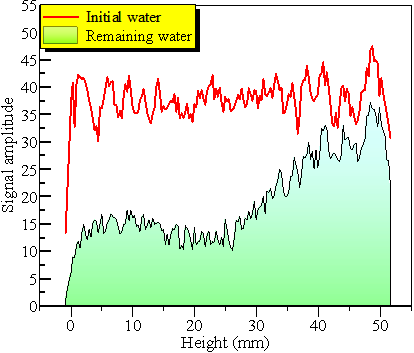

Figure 5 shows the GR results of microwave-thawed samples, reflecting the moisture distribution along the height of the sample. As microwave thawing progresses, the signal amplitude of the GR curve decreases. This indicates that the moisture content of the sample decreases after microwave heating. Furthermore, during the microwave thawing process, the moisture near the auxiliary block is removed earlier. This is determined by the thawing method introduced in Figure 1, where the thawing along the height of the sample causes moisture distribution differences along the height direction.

Dry sample

Wet sample

Saturated sample

Figure 5: GR curve of microwave-thawed samples

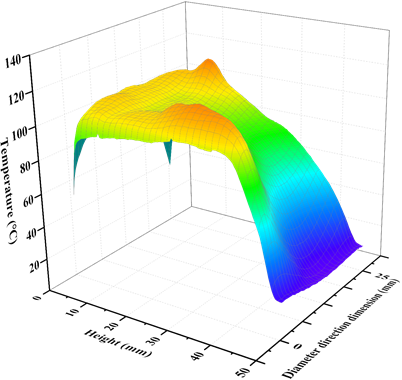

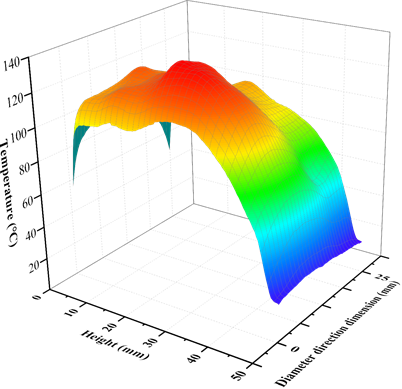

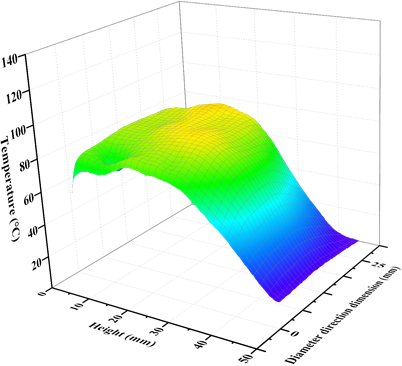

Figure 6 presents the surface temperature distribution of coal samples after microwave thawing. Deeper colors (red) represent higher temperatures, while lighter colors (blue) represent lower temperatures. The temperature in the region near the auxiliary block (height 0mm-30mm) is higher than in the area further away from the block (30mm-50mm). There is a clear temperature gradient along the height of the sample, especially in the 30mm-50mm height range. As explained by the thawing method introduced in Figure 1, the differential thawing along the height of the sample causes this variation in temperature distribution. Compared to saturated samples, the temperature distribution near the auxiliary block in wet-saturated samples is more uneven, with many red regions, where the temperature ranges from 120°C to 140°C. This indicates that when the saturation level of the coal sample is lower, high-temperature zones are more likely to appear. Overall, the temperature of wet samples is higher than that of dry and saturated samples.

Dry sample

Wet sample

Saturated sample

Figure 6: Surface temperature distribution of microwave-thawed samples

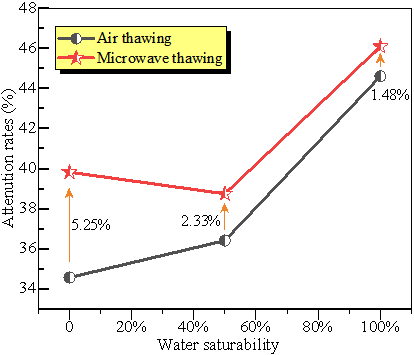

Figure 7 shows the velocity attenuation of the samples. It can be seen that as the saturation of the sample increases, the damage factor of the wave velocity of the air-thawed coal sample increases, indicating that higher saturation is favorable for liquid nitrogen fracturing of coal. This is similar to the results of the seepage pore growth rate. Under the same saturation, the damage factor of the wave velocity in microwave-thawed coal samples is higher than that in air-thawed coal samples, especially in low-saturation coal.

Figure 7: Velocity variation of the samples

This chapter analyzed the pore structure evolution, moisture changes, surface temperature distribution, and velocity attenuation of low-temperature liquid nitrogen frozen coal samples subjected to microwave thawing at different saturation levels. By comparing with air thawing, the thawing mechanism of liquid nitrogen-frozen coal samples under microwave treatment at different saturations was revealed. The main conclusions obtained are as follows:

Large-diameter Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analyzer

If you are interested in the above applications, feel free to contact: 15618820062

[1] Yang ZR, Wang CL, Zhao Y, Bi J. Microwave fracturing of frozen coal with different water content: Pore-structure evolution and temperature characteristics. Energy 2024;294(1):130938.

Phone: 400-060-3233

After-sales: 400-060-3233

Back to Top