Carbon materials are commonly used as anode materials in ion batteries. However, the theoretical capacity of commercially available graphite is nearing its theoretical limit, making further performance improvements challenging. Consequently, discovering the next generation of electrode materials for ion batteries is crucial. When used as an anode, porous carbon’s high specific surface area enables it to accommodate more ions, delivering higher capacity. Its multidimensional porous structure provides efficient diffusion pathways and short diffusion distances for ions. Defects such as vacancies and heteroatom doping serve as additional storage sites. Furthermore, the mechanical stress from volume expansion/contraction during ion insertion and extraction is minimal, ensuring excellent cycling stability. Therefore, porous carbon often exhibits superior electrochemical performance compared to traditional graphite.

Porous carbon can be categorised by pore size into microporous (pore size < 2 nm), mesoporous (2–50 nm), and macroporous (>50 nm) carbon. In the field of new energy batteries, microporous and mesoporous carbon materials are predominantly used. The preparation method and choice of precursors directly determine the material’s performance and application range. Over the past decades, extensive synergistic design and regulation have been conducted on pore size, surface chemistry, and structure of nanoporous carbon. In this study, low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF-NMR) was employed to investigate the pore size distribution of porous carbon [1].

Porous carbon materials used in batteries are more specialised than conventional porous materials. Being a powder dominated by micropores with a narrow size distribution, they are unsuitable for traditional pore size measurement methods such as mercury intrusion. Commonly employed techniques include gas adsorption and low-field NMR [2].

Gas Adsorption Method

The principle of gas adsorption for determining specific surface area relies on the adsorption properties of gases on solid surfaces. Under specific pressures, sample particles (adsorbents) physically adsorb gas molecules (adsorbates) reversibly at ultra-low temperatures. At each pressure, a specific equilibrium adsorption quantity exists. Measuring this equilibrium allows theoretical models to calculate the sample’s specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution.

Common adsorbates include nitrogen, argon, carbon dioxide, and krypton. However, the precision of nitrogen adsorption depends heavily on the equipment. Higher accuracy devices require longer measurement times, with some samples taking up to a week, making it unsuitable for modern industrial production and rapid testing requirements [3].

Low-Field NMR Method

Low-field NMR leverages hydrogen’s excellent detectability to accurately measure water signals saturated in the pores of porous carbon. By using a calibration curve, the relationship between NMR water signal and water mass is determined. This allows calculation of saturated water content, sample porosity, and, using the intrinsic surface relaxation rate and T2 relaxation spectrum models, rapid determination of pore size distribution.

Compared with gas adsorption, low-field NMR offers a significant speed advantage, reducing measurement times from tens of minutes or even a week to under 2 minutes. It is non-destructive and allows repeated testing [4].

Using low-temperature LF-NMR, porous carbon porosity is measured, and under known surface relaxation rates, pore size distribution is rapidly obtained.

The experimental procedure is as follows:

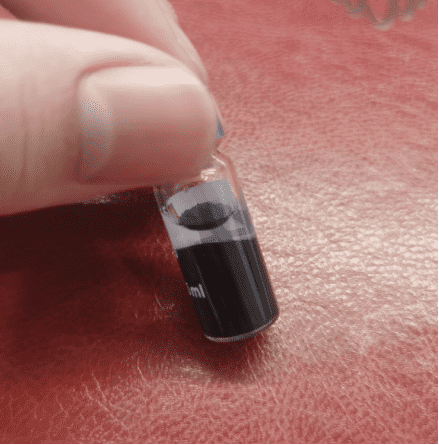

1. Take a chromatography vial, use a pipette to add approximately 1 ml of water, and measure the tare weight.

2. For the four porous carbon samples sent by the client, add an appropriate amount of each into separate chromatography vials with water. Gently shake until the carbon is fully immersed, then weigh to record the net mass of porous carbon added.

3. Place the vials in a vacuum saturation apparatus to evacuate air from the pores, allowing them to fill completely with water. The water in the pores serves as the detection target for measuring porosity and pore size distribution.

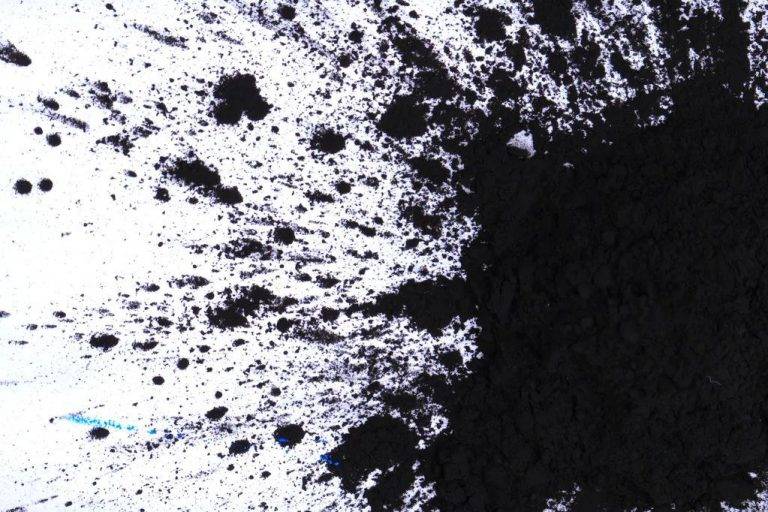

Vacuum-treated porous carbon sample

4. After vacuum treatment, transfer the samples to the NMR instrument. Using liquid nitrogen, stabilise the temperature at -6°C, calibrate the frequency, then measure the samples to obtain NMR results.

5. Perform calibration tests with standards (NMR results are relative and require correlation with known standards) and baseline measurements.

6. Establish the calibration curve to convert NMR signals into porosity.

7. Input the porosity into software to calculate the pore size distribution of porous carbon.

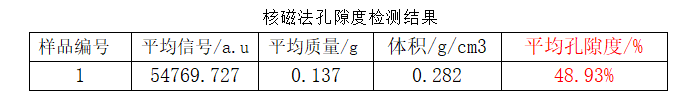

The porosity measurement for a sample using NMR is as follows:

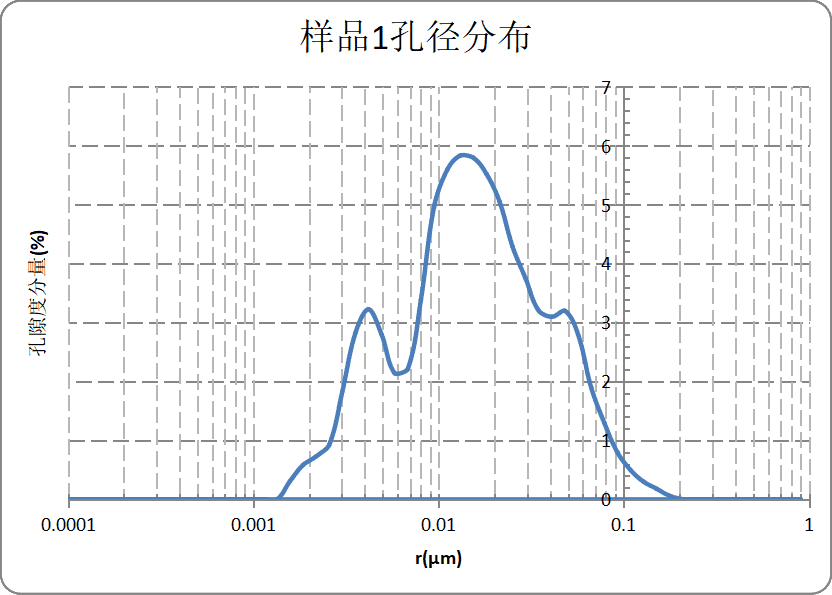

The pore size distribution for the same sample is as follows:

NMR-determined pore size distribution

The pore size distribution peak for the same porous carbon sample is shown below:

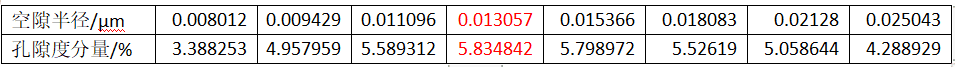

Using software modelling, the LF-NMR method fully presents the pore size distribution of the sample. The porosity is 48.93%, with the main distribution peak at 13 nm corresponding to a pore fraction of 5.83% (highlighted in red in the table above).

Low-Field NMR Method

Low-field NMR provides rapid measurement of porous carbon porosity and pore size distribution, ideal for modern industrial production. It enables fast testing, selection of optimised production processes and formulations, and comparison across different batches. By identifying samples with larger pore sizes, these materials can be used as battery anodes to provide more effective diffusion pathways and additional ion storage sites, ultimately enhancing battery performance.

[1] Xia W, Mao Y, Xie G, et al. Role of sodium oleate in the in-situ pore wetting of porous active carbon by 1H LF-NMR: Implications for porous mineral flotation[J]. Powder Technology, 2021, 392:116-122.

[2] Wang A, Chen W, Liu S, et al. Layered porous carbon material derived from food residues and its application for elemental mercury adsorption in flue gas[J]. Fuel, 2023, 335:126876-.

[3] Toshihide, Horikawa, Noriyuki, et al. Preparation of nitrogen-doped porous carbon by ammonia gas treatment and the effects of N-doping on water adsorption[J]. Carbon: An International Journal Sponsored by the American Carbon Society, 2012, 50(5):1833-1842.

[4] Mao Y, Xie G. Relationship model between pore wetting and floatability of active carbon: Potential guidance on porous mineral flotation[J]. Minerals Engineering, 2020, 157(1).

Phone: 400-060-3233

After-sales: 400-060-3233

Back to Top